Mahan Moalemi is a writer, curator, and doctoral candidate in the Department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies at Harvard University. He is the co‑editor of Ethnofuturisms (Merve Verlag, 2018), and his writings have appeared in Art in America, Cabinet, Domus, e-flux Criticism, frieze, MoMA’s post, and in several exhibition catalogues, artist monographs, and academic anthologies. He has held curatorial positions at the Harvard Art Museums and the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, and is currently a visiting adjunct professor in the Master of Fine Arts program at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

2025

⚫️ A Queer Media Archaeology of the Future: Ming Wong’s Quest for a Cantonese Space Opera Film

⚫️ Exquisite Crops: Stephanie Comilang’s Science Fiction Documentaries

⚫️ Hygiene — Stress Management — Procrastination

2024

⚫️ A System of Gaps and Linkages: On Sarah Oppenheimer’s Art Practice and Pedagogy

2023

⚫️ Beyond Hope

⚫️ This Machine Creates Opacities: Pope.L’s Corbu Pops

⚫️ Solid Projections: Beth Collar, Coleman Collins, Nevine Mahmoud, and Jeffrey Stuker

⚫️ Remediations: Shireen Hamza, Elitza Koeva, Chrystel Oloukoï, Pauline Shongov, and Emilio Vavarella

2022

⚫️ A Carrier Bag Theory of Friction and Other Haptic Dramas: On the Films of Maryam Tafakory

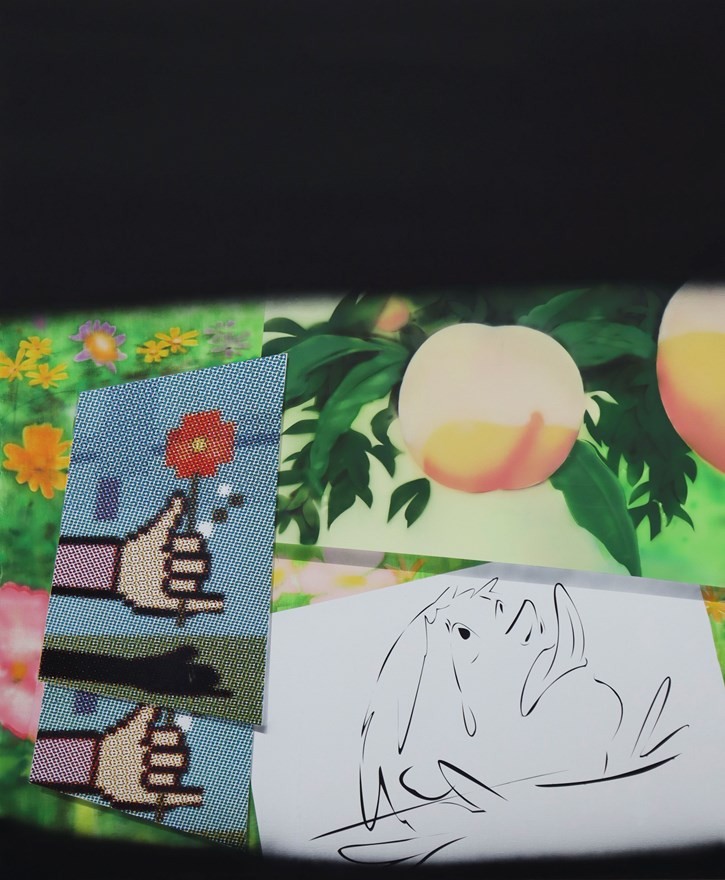

⚫️ Evoking the Space of the Screen: On the Paintings of Hoda Kashiha

⚫️ Archived Opposition: “Art for the Future”

2021

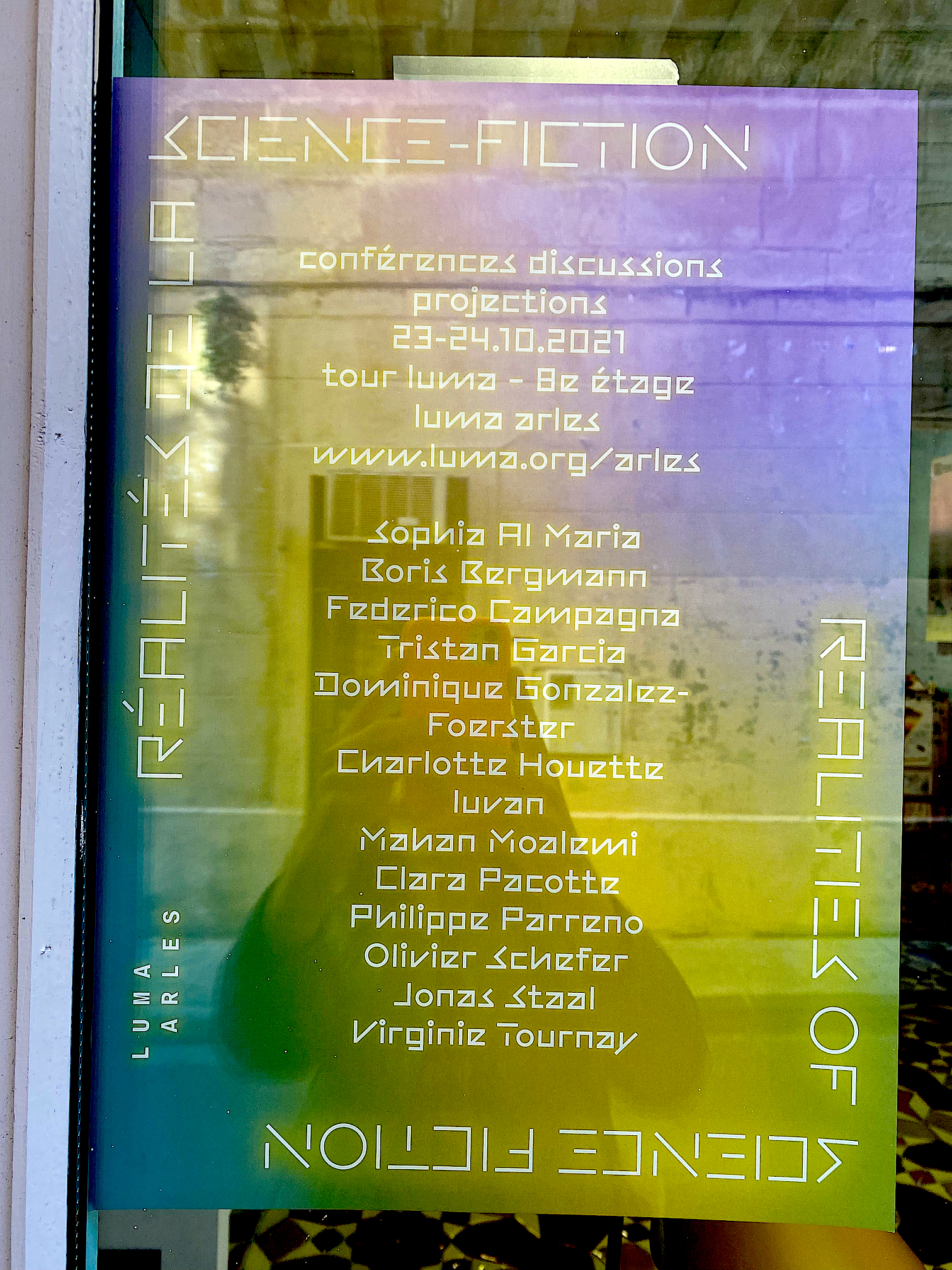

⚫️ Ethnofuturity and the Many Ends of (World) History

⚫️ An Introduction to Ethnofuturisms

⚫️ The Geopolitical Ontology of the Post-Optical Image: Notes on The Otolith Group’s Sovereign Sisters

⚫️ Earthbound: Notes on Sahej Rahal’s Bashinda

⚫️ Fucking with the Human Outline: Notes on Zach Blas’s SANCTUM

2020

⚫️ Notes on the Hungarofuturist Manifesto

⚫️ Notes on Class, Labor, and the Moving Image

2019

⚫️ Toward a Comparative Futurism

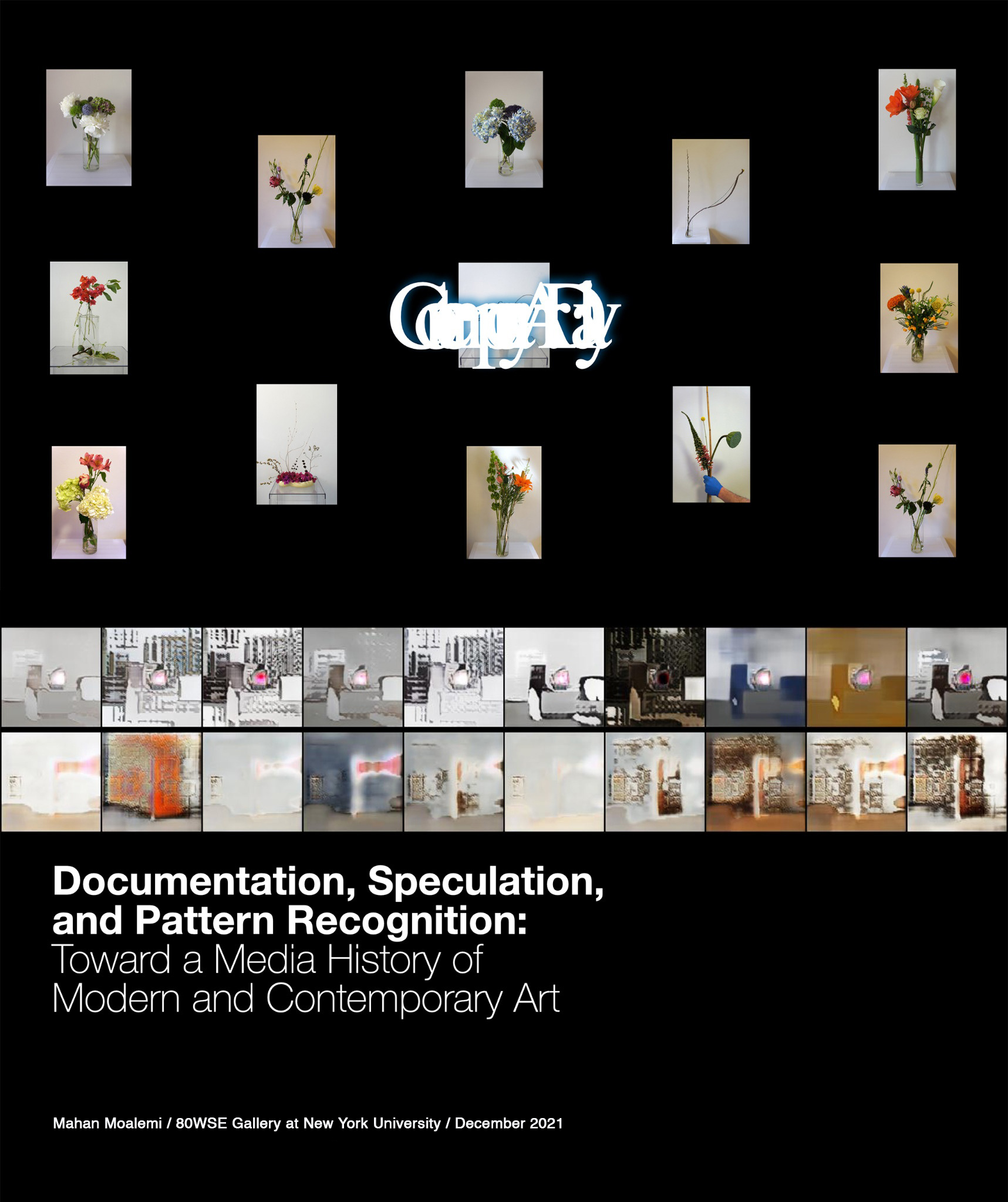

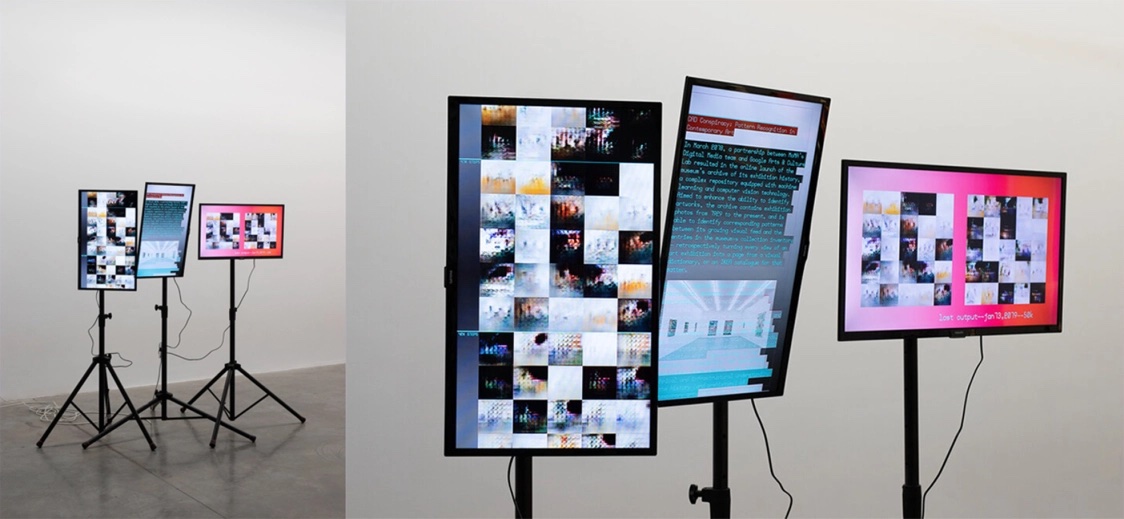

⚫️ On the Installation Shots of Contemporary Art Exhibitions

⚫️ “Altered Inheritances”: Shilpa Gupta and Zarina

⚫️ The Spark Is You: On the Works of Morteza Ahmadvand, Ghazaleh Hedayat, and Sahand Hesamiyan

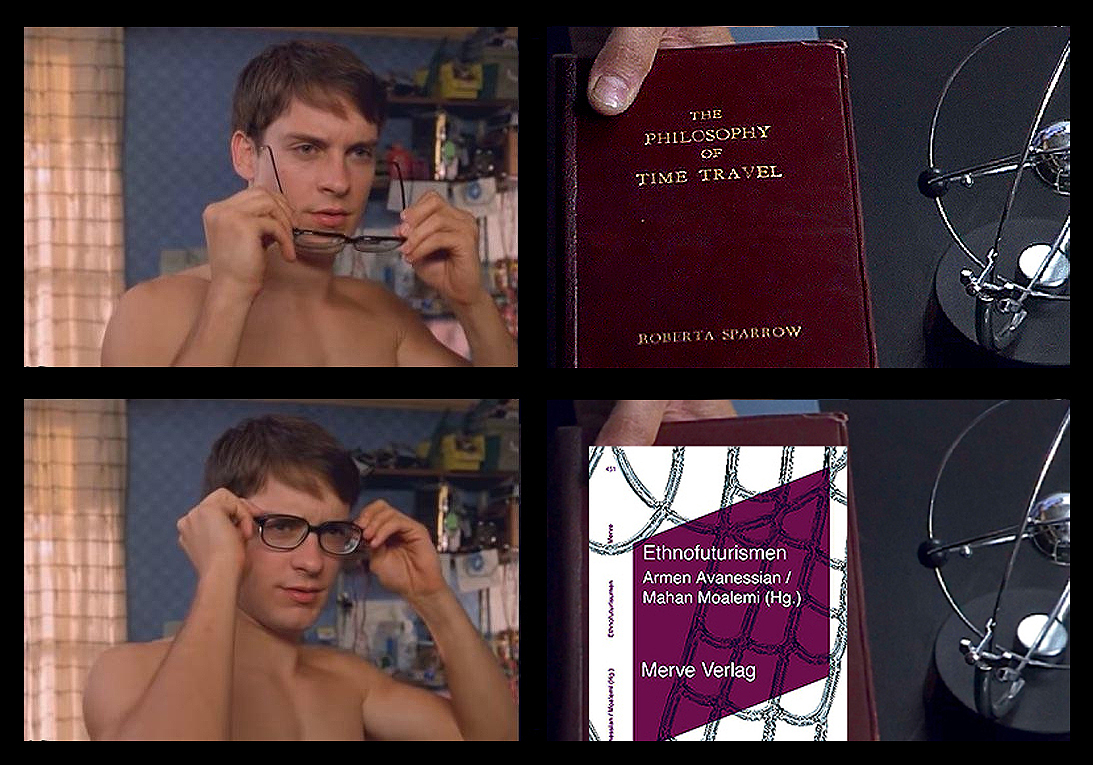

⚫️ Ethics of Time Travel: Toward a Comparative Futurism

⚫️ CAD Conspiracy: Pattern Recognition in Contemporary Art

2018

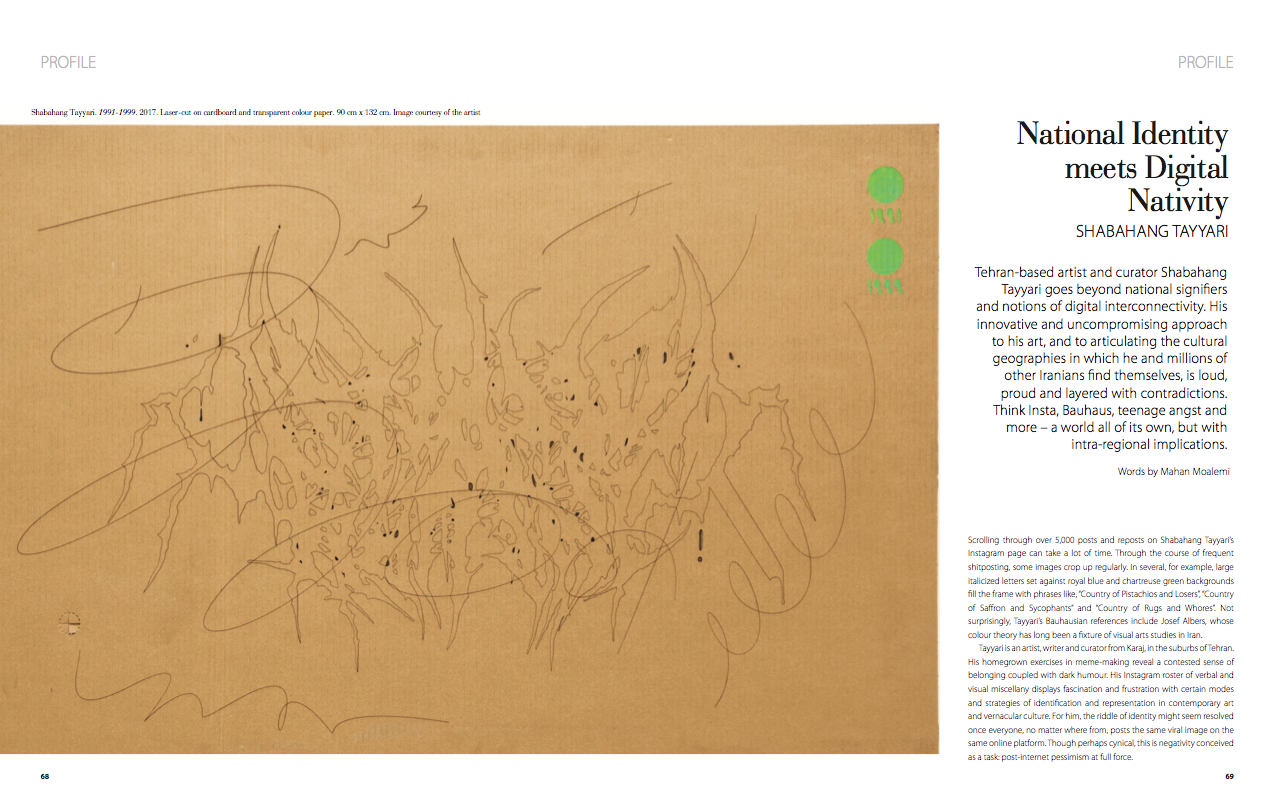

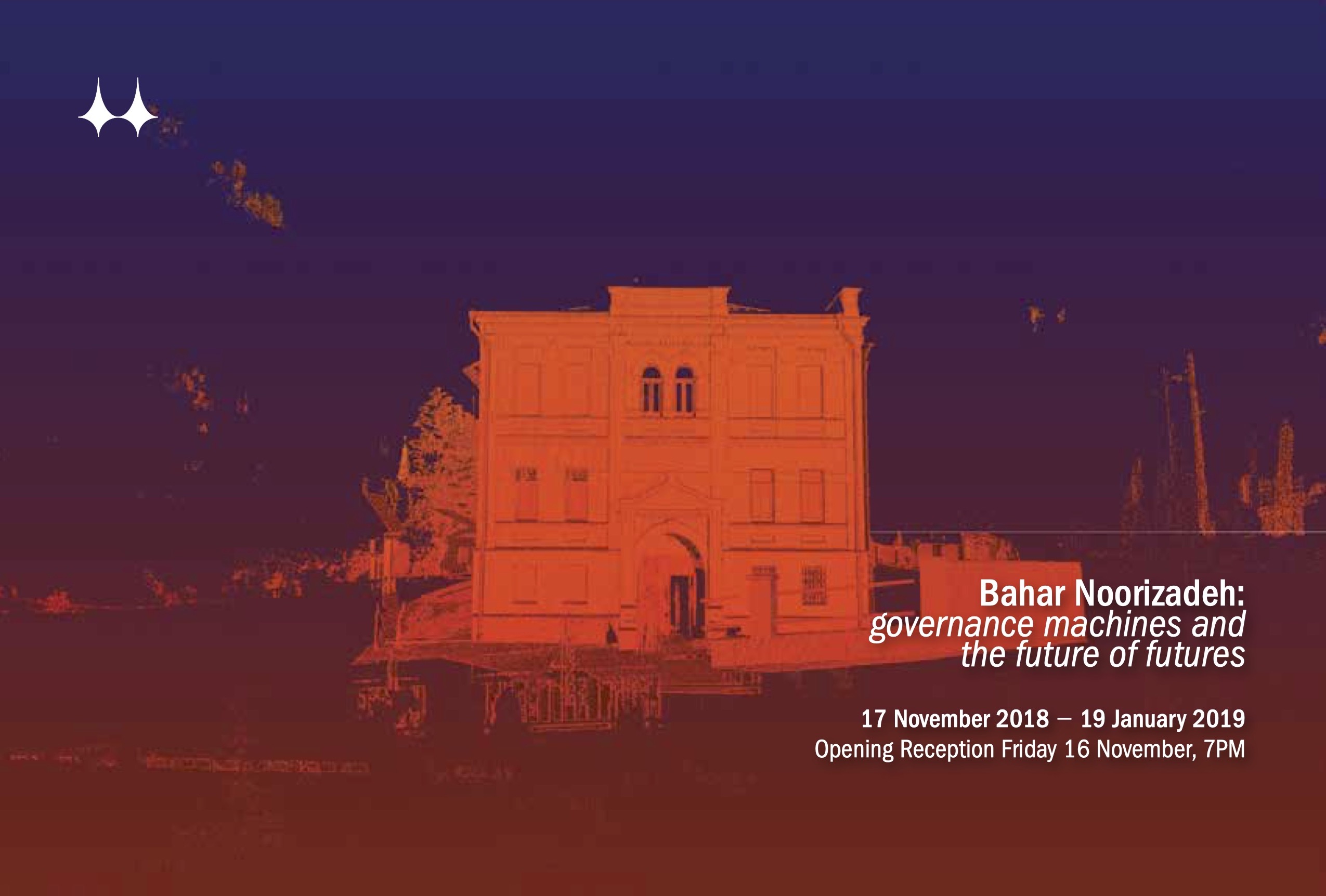

⚫️ Peer Pressuring the Past, Future-Fictioning the Present: On the Films of Bahar Noorizadeh

⚫️ A Butterfly Effect Across the Chronosphere

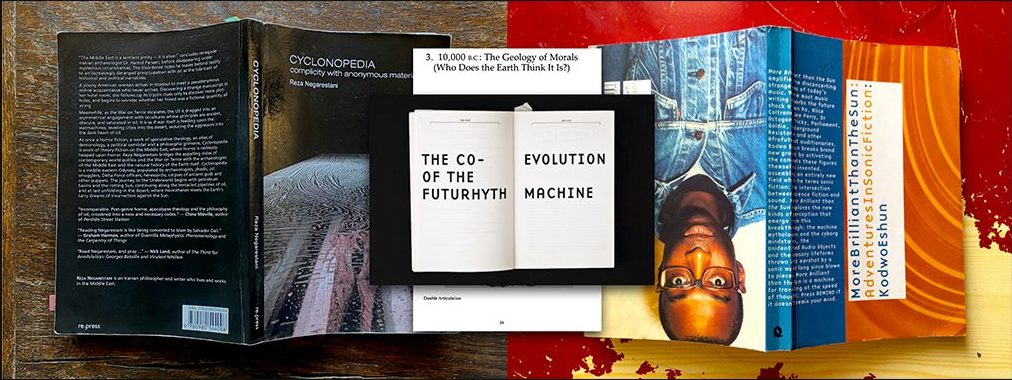

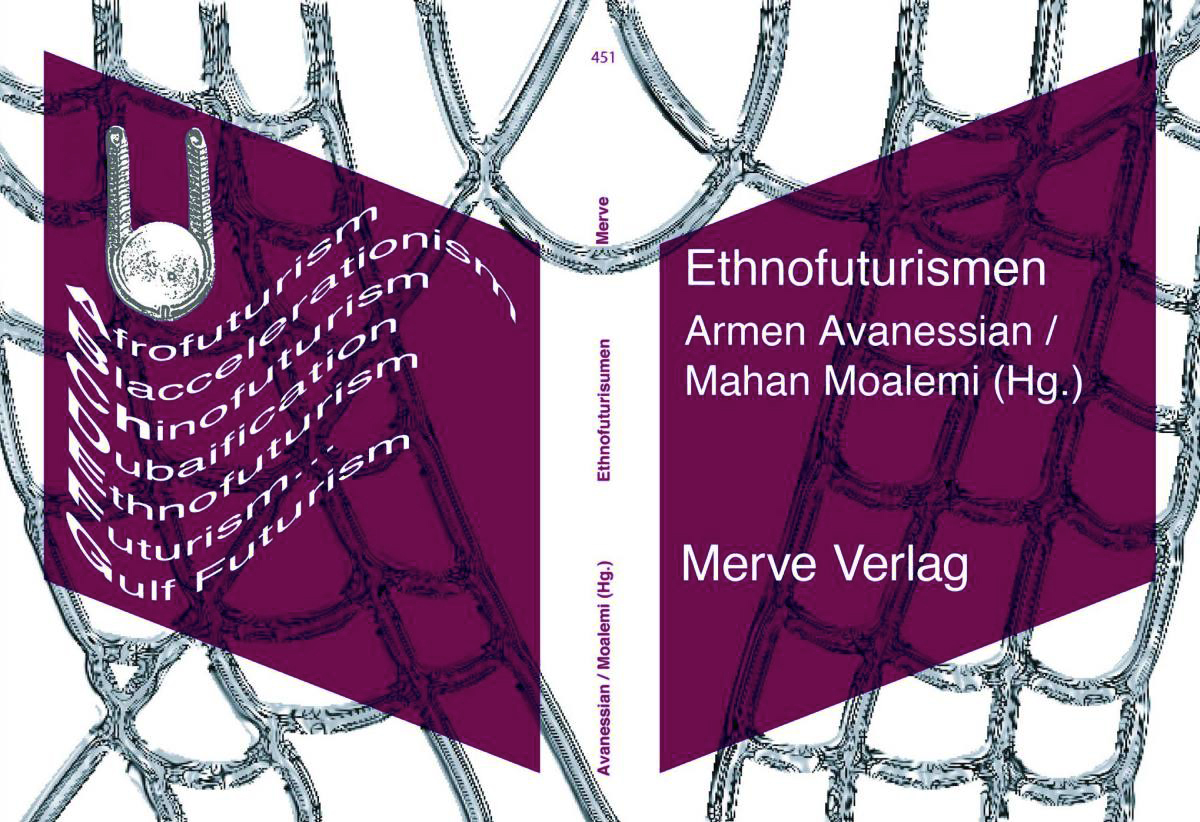

⚫️ Ethnofuturisms (Leipzig: Merve Verlag)

⚫️ Notes From the Attic: Displaying the Material History of the CIA

⚫️ EXIT: A Postcard from Tehran

2017

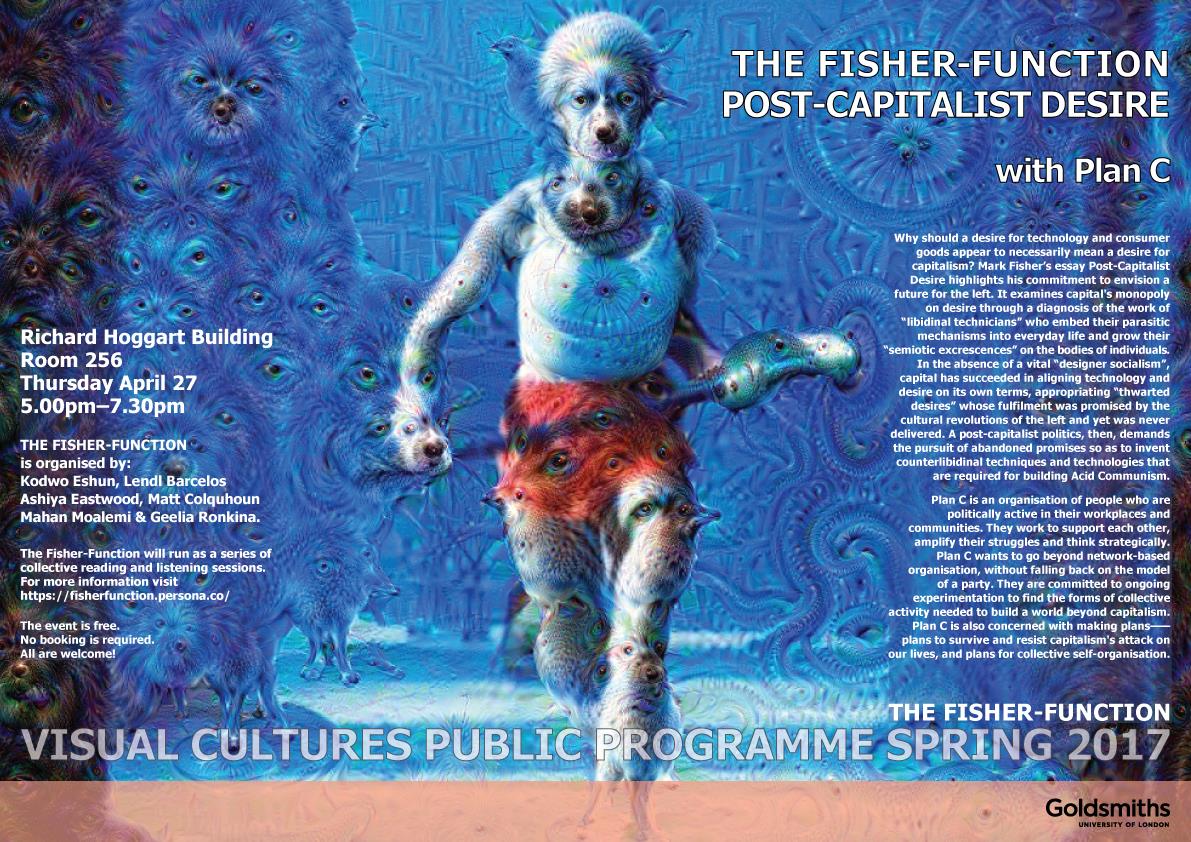

⚫️ “Post-Capitalist Desire”: An Introduction

⚫️ The Exhibition Whisperer: Auto-Italia South East and Image-Sharing Technologies

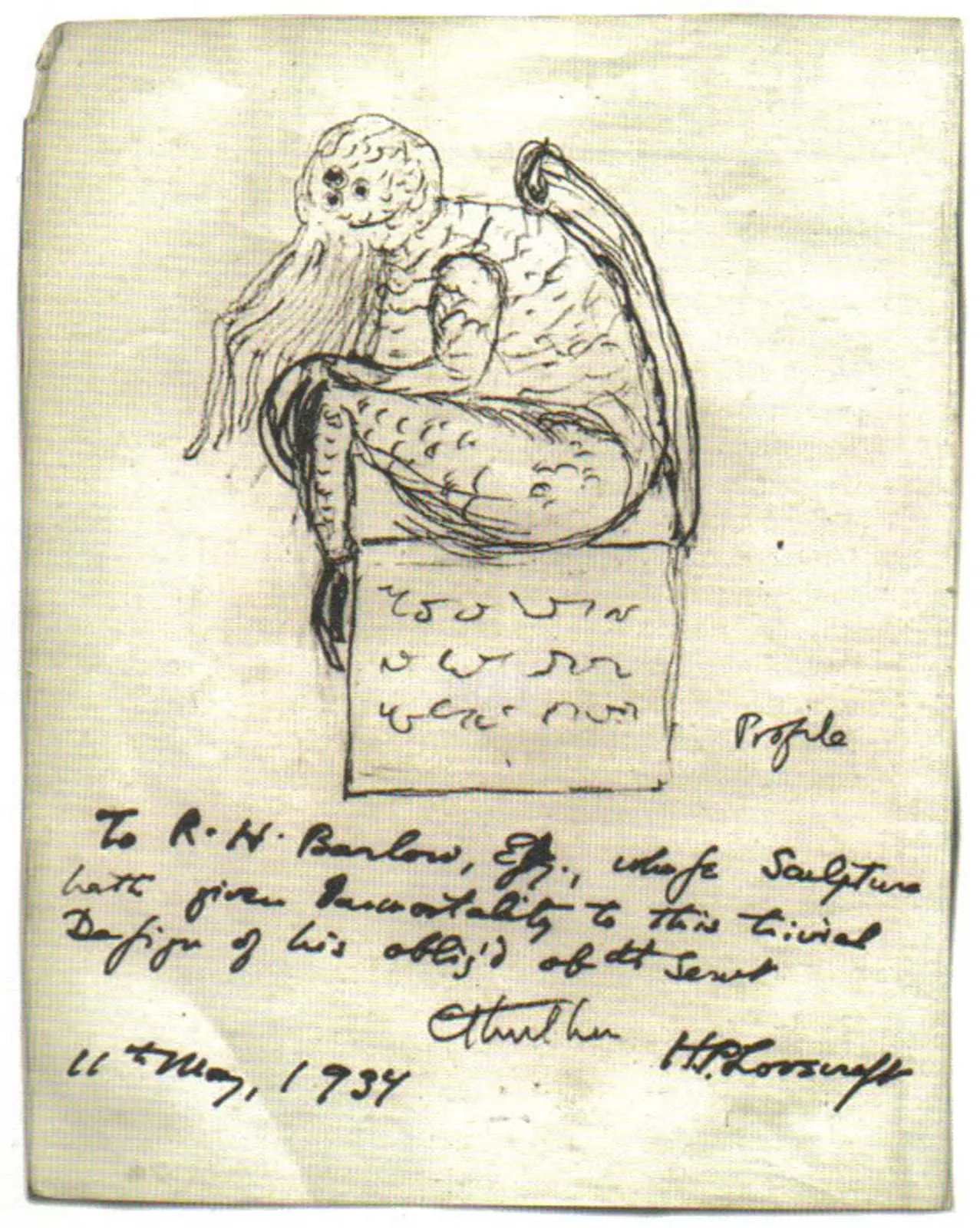

⚫️ Instrumental Xenotation: H. P. Lovecraft, Susan Sontag, Linda Trent, Walter Benjamin, and Tom Ford

⚫️ Objective Hyperreality vs. Hyperobjective Reality

2016

⚫️ August 3, 2016: After Pak Sheung-Chuen

⚫️ Trans-Temporal Perspectives

⚫️ An Alternative Entry in Five Moves